- In the paediatric basic life support sequence, rescuers should perform assessment for signs of life (circulation) simultaneously with breathing assessment and during the delivery of rescue breaths.

- If there are no signs of life, chest compressions should be started immediately after rescue breaths have been delivered.

- There is emphasis on rescuers using mobile phones with speaker function to facilitate bystander access to dispatcher guided cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and to summon emergency medical services (EMS) without leaving the child or infant.

- In certain situations, such as when the child or infant is breathing spontaneously but requires airway management or when the child has a traumatic injury, the recovery position is not recommended. In these circumstances:

- Keep the patient flat, maintain an open airway by either continued head tilt and chin lift or jaw thrust.

- For trauma victims, leave the child or infant lying flat and open and maintain the airway using a jaw thrust, taking care to avoid spinal movement.

- High quality CPR is emphasised:

- chest compression depth at least one third the anterior-posterior diameter of the chest, or by 4 cm for the infant and 5 cm for the child.

- chest compression pauses minimised so that 80% or more of the CPR cycle is comprised of chest compressions

- chest compression rate 100-120 min-1

- allow full recoil of the chest after each chest compression.

Guidelines 2021 are based on the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation 2020 Consensus on Science and Treatment Recommendations and the European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation (2021). Refer to the ERC guidelines publications for supporting reference material.

- Management of cardiac arrest in patients with known or suspected COVID-19 is not specifically included in these guidelines, but is covered within RCUK’s COVID-19 guidance which is accessible from the RCUK website.

The process used to produce the Resuscitation Council UK Guidelines 2021 is accredited by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). The guidelines process includes:

- Systematic reviews with grading of the certainty of evidence and strength of recommendations. This led to the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations.

- The involvement of stakeholders from around the world including members of the public and cardiac arrest survivors.

- Details of the guidelines development process can be found in the Resuscitation Council UK Guidelines Development Process Manual.

This guideline applies to all infants and children excluding newborn infants (unless no other option is available at birth)

- A newborn is an infant just after birth.

- An infant is under the age of 1 year.

- A child is between 1 year and 18 years of age.

- The differences between adult and paediatric resuscitation are largely based on differing aetiology. if the rescuer believes the victim to be a child then they should use the paediatric guidelines. If a misjudgement is made, and the victim turns out to be a young adult, little harm will accrue as studies of aetiology have shown that the paediatric causes of arrest continue into early adulthood.

- It is necessary to differentiate between infants (under 1 year of age) and children, as there are some important differences between these two groups.

High quality paediatric basic life support (BLS) is the cornerstone of resuscitation.

- Regular training in paediatric BLS is essential as cardiorespiratory arrest occurs less frequently in children than in adults; thus, both healthcare professionals and members of the public are less likely to be involved in paediatric resuscitation.

- The ideal interval for re-training is unknown but it is likely that frequent top ups, several times a year, are more effective.

The sequence of actions in paediatric BLS will depend upon the level of training of the rescuer attending:

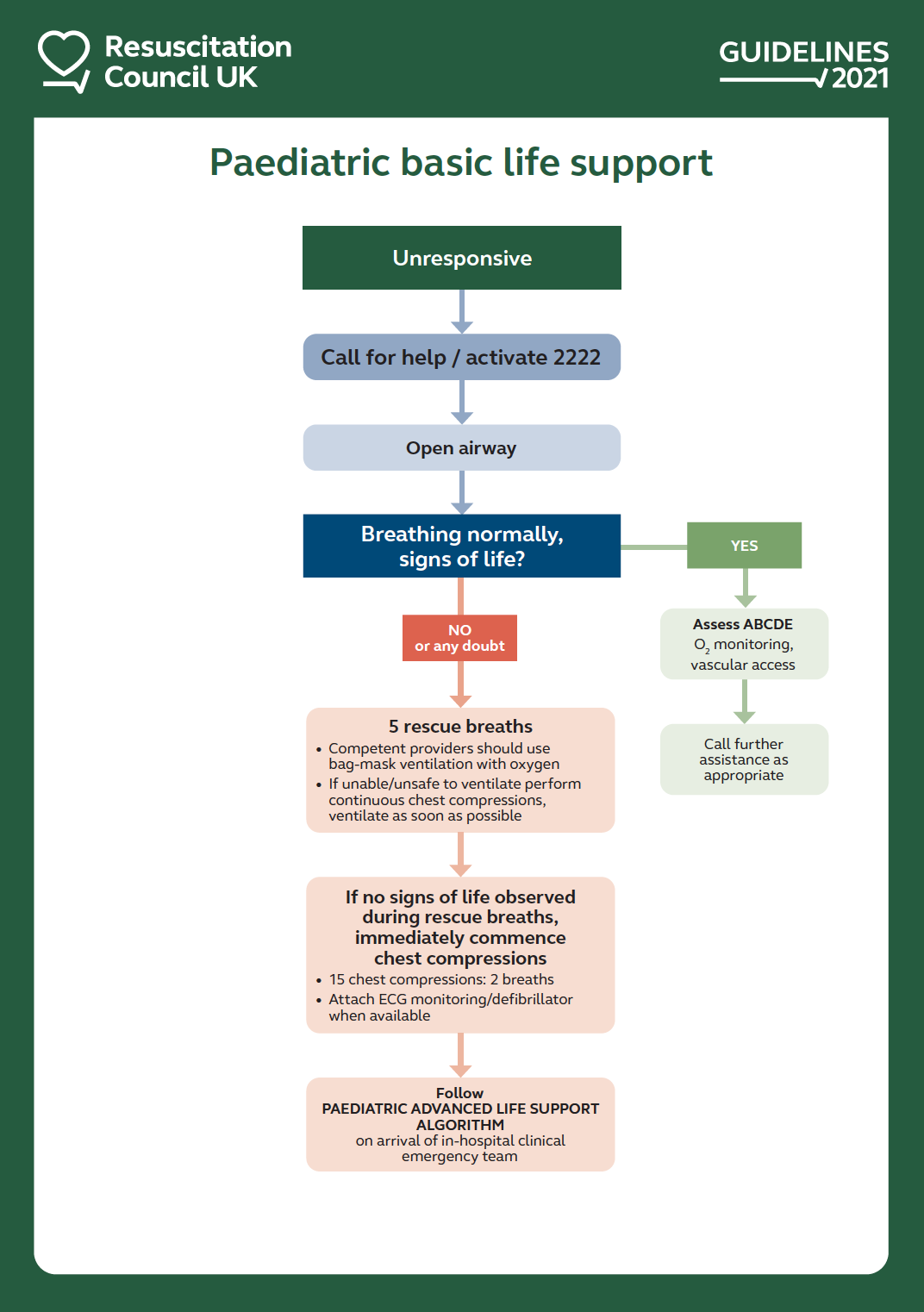

- Healthcare professionals with a duty to respond to paediatric emergencies should be fully competent in paediatric BLS; a specific paediatric BLS algorithm is presented as they have an obligation to deliver more comprehensive care.

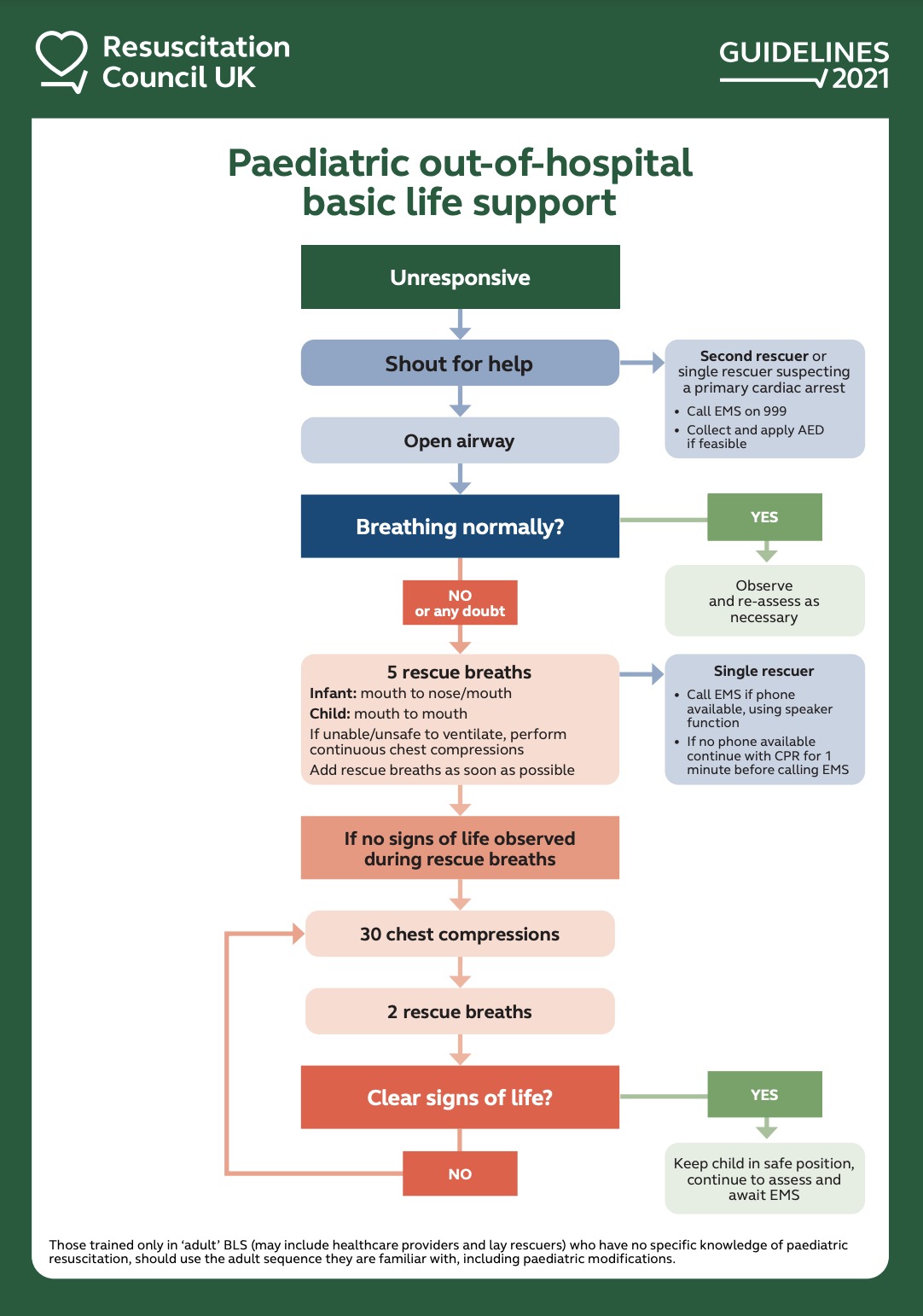

- Those trained only in adult BLS (may include healthcare providers and members of the public) who have no specific knowledge of paediatric resuscitation, should use the adult sequence they are familiar with, including the paediatric modifications if possible (see below).

- Those untrained (dispatcher-assisted members of the public).

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should start as soon as possible for optimum outcome.

- This should start with the first person on scene, who is often a bystander (i.e. a member of the public).

The majority of paediatric cardiorespiratory arrests are not caused by primary cardiac problems

- Paediatric cardiorespiratory arrests are usually secondary to other causes, usually hypoxia - hence the order of delivering the resuscitation sequence: Airway (A), Breathing (B) and Circulation (C).

Recognition of cardiorespiratory arrest: healthcare provider and members of the general public

- If a member of the general public or healthcare provider considers that there are no ‘signs of life’, and the child or infant exhibits abnormal or absent breathing, CPR should be started immediately.

- The presence or absence of ‘signs of life’, such as response to stimuli, normal breathing (rather than abnormal gasps) or spontaneous movement must be looked for during the breathing assessment and during rescue breathing to determine the need for chest compressions. If there is still doubt at the end of the rescue breaths, start CPR.

- Feeling for a pulse is not a reliable way to determine if there is an effective or inadequate circulation, and palpation of the pulse is not the determinant of the need for chest compressions.

- Rescuers are no longer taught to feel for a pulse as part of the assessment of need for chest compressions in BLS.

- If a healthcare provider does feel for a pulse in an unresponsive child, they must be certain that one is present for them NOT to start CPR. In this situation, there are often other signs of life present.

Compression: Ventilation (C:V) ratios:healthcare provider and members of the public

- Although ventilation remains a particularly important component of CPR in children, rescuers who are unable or unwilling to provide breaths should be encouraged to perform at least compression-only CPR. A child is far more likely to be harmed if the bystander does nothing.

- CPR should be started with the C:V ratio that is familiar and, for most, this will be 30:2.

- The paediatric modifications to adult CPR should be taught to those who care for children but are unlikely to have to resuscitate them.

- The specific paediatric sequence incorporating the 15:2 ratio is primarily intended for healthcare professionals with a duty to respond to paediatric emergencies.

Chest compression quality

- Uninterrupted, high quality chest compressions are vital, with attention being paid to all components of each chest compression including the rate, depth and allowing adequate time for chest recoil to occur (avoiding lean on the chest). Approximately 50% of the whole chest compression cycle should be the relaxation phase (one cycle is from the start of one compression to the next). Chest compression pauses should be minimised so that 80% or more of the CPR cycle is comprised of chest compressions.

- Training and feedback devices have been developed for adults and children.

- Measurement data indicate that the approximate dimensions of one-third compression depths of the chest in infants and children are about 4 cm and 5 cm respectively.

- To maintain consistency with adult BLS guidelines, the compression rate remains at 100–120 min-1

- Chest compressions should be delivered on a firm surface otherwise the depth of compression may be difficult to achieve and will be inaccurate if a feedback device is being used.

Those with a duty to respond to paediatric emergencies (usually healthcare professional teams) should use the following sequence:

- Ensure the safety of rescuer and child.

- Check the child’s responsiveness:

- Gently stimulate the child and ask loudly, ‘Are you alright?’

If the child responds by answering or moving:

- Leave the child in the position in which you find them (provided they are not in further danger).

- Check their condition and get help if needed.

- Reassess the child regularly.

If the child does not respond:

- Shout for help.

- In cases where there is more than one rescuer, a second rescuer should call 999 (outside hospital) to summon emergency medical services (EMS) or call 2222 if in an NHS hospital to summon the clinical emergency team immediately. If calling 999 preferably use the speaker function of a mobile phone.

- Turn the child onto their back and open the airway using head tilt and chin lift:

- Place your hand on their forehead and gently tilt their head back.

- With your fingertip(s) under the point of the child’s chin, lift the chin. Do not push on the soft tissues under the chin as this may block the airway.

- If you still have difficulty in opening the airway, try the jaw thrust method: place the first two fingers of each hand behind each side of the child’s mandible (jawbone) and push the jaw forward (towards you).

- Have a low threshold for suspecting injury to the neck. If you suspect this, try to open the airway using jaw thrust alone. If this is unsuccessful, add head tilt gradually until the airway is open. Establishing an open airway takes priority over concerns about the cervical spine.

- Keeping the airway open, look, listen, and feel for abnormal/absent breathing by putting your face close to the child’s face and looking along the chest whilst simultaneously looking for signs of life.

- Look for chest movements:

- Listen at the child’s nose and mouth for breath sounds.

- Feel for air movement on your cheek.

- In the first few minutes after cardiac arrest a child may be taking infrequent, noisy gasps. Do not confuse this with normal breathing.

- Look, listen, and feel for no more than 10 seconds before deciding – if you have any doubts whether breathing is normal, act as if it is not normal.

- Simultaneously look for signs of life (these include any movement, coughing, or normal breathing).

(Note: Studies have shown how unreliable feeling for a pulse is in determining presence or absence of a circulation even for trained paediatric healthcare workers, hence the importance of the need to look for signs of life. However, if a healthcare worker wishes to also check for a pulse this should be done simultaneously with the breathing assessment).

If the child IS breathing normally:

- Consider turning the child onto their side into the recovery position (see below) or maintain an open airway with head tilt – chin lift or jaw thrust.

- Send or go for help – call the relevant emergency number on your mobile phone where possible. Only leave the child if no other way of obtaining help is possible.

- Check for continued normal breathing.

If the child’s breathing is abnormal or absent

- Give 5 initial rescue breaths.

- Although rescue breaths are described here, it is common in healthcare environments to have access to bag-mask devices and providers trained in their use should use them as soon as they are available. In larger children when BMV is not available, competent providers can also use a pocket mask for rescue breaths.

- While performing the rescue breaths, note any gag or cough response to your action. These responses, or their absence, will form part of your ongoing assessment of ‘signs of life’

- Rescue breaths for an infant:

- Ensure a neutral position of the head (as an infant’s head is usually flexed when supine, this may require some gentle extension) and apply chin lift.

- Take a breath and cover the mouth and nose of the infant with your mouth, making sure you have a good seal.

- If the nose and mouth cannot both be covered in the older infant, the rescuer may attempt to seal only the infant’s nose or mouth with their mouth (if the nose is used, close the lips to prevent air escape).

- Blow steadily into the infant’s mouth and nose over 1 second sufficient to make the chest rise visibly. This is the same time period as in adult practice.

- Maintain head position and chin lift, take your mouth away, and watch for their chest to fall as air comes out.

- Take another breath and repeat this sequence four more times.

- Rescue breaths for a child over 1 year:

- Ensure head tilt and chin lift; extending the head into 'sniffing’ position.

- Pinch the soft part of the nose closed with the index finger and thumb of your hand on their forehead.

- Open the mouth a little but maintain the chin lift.

- Take a breath and place your lips around the mouth, making sure that you have a good seal.

- Blow steadily into their mouth over 1 second sufficient to make the chest rise visibly.

- Maintaining head tilt and chin lift, take your mouth away and watch for the chest to fall as air comes out.

- Take another breath and repeat this sequence four more times.

- Identify effectiveness by seeing that the child’s chest has risen and fallen in a similar fashion to the movement produced by a normal breath.

For both infants and children, if you have difficulty achieving an effective breath, the airway may be obstructed:

- Open the child’s mouth and remove any visible obstruction. Do not perform a blind finger sweep.

- Ensure that there is adequate head tilt and chin lift but also that the neck is not over extended; try repositioning the head to open the airway.

- If head tilt and chin lift has not opened the airway, try the jaw thrust method.

- Make up to 5 attempts to achieve effective breaths. If still unsuccessful, move on to chest compressions.

Note:

- If there is only one rescuer, with a mobile phone, they should call for help (and activate the speaker function) immediately after the initial rescue breaths. Proceed to the next step while waiting for an answer. If no phone is readily available perform one minute of CPR before leaving the child.

- In cases where paediatric BLS providers are unable or unwilling to start with ventilations, they should proceed with compressions and add ventilations into the sequence when able (another provider, equipment available).

Following the rescue breaths, if you are confident that you can detect signs of life:

- Continue rescue breathing, if necessary, until the child starts breathing effectively on their own.

- Unconscious children and infants who are not in cardiac arrest and clearly have normal breathing, can have their airway kept open by either continued head tilt - chin lift or jaw thrust or, when there is a perceived risk of vomiting, by positioning the unconscious child in a recovery position.

- Re-assess the child frequently.

Following the rescue breaths, if there are no signs of life or if you are unsure:

- Start good quality chest compressions.

- Rate: 100-120 min-1 for both infants and children.

- Depth: depress the lower half of the sternum by at least one third of the anterior–posterior dimension of the chest (which is approximately 4 cm for an infant and 5 cm for a child).

- Compressions should never be deeper than the adult 6 cm limit (approx. an adult thumb’s length).

- Release all pressure on the chest between compressions to allow for complete chest recoil and avoid leaning on the chest at the end of a compression.

- Allow adequate time for chest recoil to occur (approximately 50% of the whole cycle should be the relaxation phase, i.e., from the start of one compression to the next).

- Chest compression pauses should be minimised so that 80% or more of the CPR cycle is comprised of chest compressions.

- For all children, compress the lower half of the sternum:

- To avoid compressing the upper abdomen, locate the xiphisternum by finding the angle where the lowest ribs join the sternum (breastbone).

- Compress the sternum one finger’s breadth above this.

- After each compression, release the pressure completely then repeat at a rate of 100–120 min-1.

- Allow the chest to return to its resting position before starting the next compression.

- After 15 compressions, tilt the head, lift the chin, and give rescue breaths.

- Continue compressions and breaths in a ratio of 15:2.

- Perform compressions on a firm surface.

- The best method for compression varies slightly between infants and children.

Chest compression in infants:

- Preferably use a two-thumb encircling technique for chest compression in infants – be careful to ensure complete chest recoil after each chest compression. Single rescuers might alternatively use a two-finger technique.

- The encircling technique:

- Place both thumbs flat, side-by-side, on the lower half of the sternum (as above), with the tips pointing towards the infant’s head.

- Spread the rest of both hands, with the fingers together, to encircle the lower part of the infant’s rib cage with the tips of the fingers supporting the infant’s back. Press down on the lower sternum with your two thumbs to depress it at least one-third of the depth of the infant’s chest, approximately 4 cm.

- For small infants, you may need to overlap your thumbs to provide effective compressions.

- Two finger technique: Compress the lower sternum with the tips of two of your fingers (index and middle fingers) by at least one-third of the depth of the infant’s chest, approximately 4cm.

Chest compression in children aged over 1 year:

- Place the heel of one hand over the lower half of the sternum (as above).

- Lift the fingers to ensure that pressure is not applied over the child’s ribs.

- Position yourself vertically above the victim’s chest and, with your arm straight, compress the sternum by at least one-third of the depth of the chest, approximately 5 cm.

- In larger children, or for small rescuers, this may be achieved more easily by using both hands with the fingers interlocked.

Note: Do not interrupt CPR at any moment unless there are clear signs of life (movement, coughing, normal breathing). Two or more rescuers should alternate who is performing chest compressions frequently; the compressing rescuer should switch hands (the hand compressing, the hand which is on top) or the technique (one to 2-handed) to avoid fatigue.

Continue resuscitation until:

- the child shows signs of life (e.g., normal breathing, cough, movement)

- additional qualified help arrives

- you become exhausted.

When to call for assistance

- It is vital for rescuers to get help as quickly as possible when a child collapses:

- In cases where there is more than one rescuer, a second rescuer should call the EMS immediately upon recognition of unconsciousness, preferably using the speaker function of a mobile phone.

- If there is only one rescuer, with a mobile phone, they should call help first (and activate the speaker function) immediately after the initial rescue breaths. Proceed to the next step while waiting for an answer.

- If no mobile phone is available and more than one rescuer is available, one (or more) person starts resuscitation while another goes for assistance.

- If only one rescuer is present without a mobile phone, undertake resuscitation for about 1 minute before going for assistance. To minimise interruptions in CPR, it may be possible to carry an infant or small child whilst summoning help.

- The only exception to performing 1 minute of CPR before going for help is in the unlikely event of a child with a witnessed, sudden collapse when the rescuer is alone with no phone and primary cardiac arrest is suspected. In this situation, a shockable rhythm is likely and the child may need defibrillation. Seek help immediately if there is no one to go for you.

Paediatric BLS modified

Adult sequence with paediatric modifications

- Rescuers who have been taught adult BLS, and have no specific knowledge of paediatric resuscitation, should use the adult sequence.

- The paediatric modifications to adult CPR should be taught to those who care for children but are unlikely to have to resuscitate them.

- Give 5 rescue breaths before starting chest compression.

- If you are on your own, perform CPR for 1 min before going for help.

- Compress the chest by at least one-third of its depth, approximately 4 cm for an infant and approximately 5 cm for an older child. Use both thumbs or two fingers for an infant under 1 year; use one or two hands for a child over 1 year as required to achieve an adequate depth of compression.

- The compression rate should be 100–120 min-1.

Dispatcher-directed CPR

- Bystander CPR should be started in all cases when feasible. The EMS dispatcher has a crucial role in assisting untrained bystanders to recognise cardiac arrest and provide CPR. When bystander CPR is already in progress at the time of the call, dispatchers may only provide instructions when asked for, or when issues with knowledge or skills are identified.

- The steps of the algorithm for paediatric dispatcher-assisted CPR are very similar to the paediatric BLS algorithm. To decrease the number of changes in rescuer position, a 30:2 C:V ratio might be preferable for a lone rescuer. If bystanders cannot provide rescue breaths, they should proceed with chest compressions only. A child or infant is far more likely to be harmed if the bystander does nothing.

Recovery position

- For children and infants with a decreased level of consciousness who do not meet the criteria for the initiation of rescue breathing or chest compressions (CPR), the recovery position may be recommended. The following describes one method of achieving a left lateral position:

- Kneel beside the child and make sure that both legs are straight.

- Place the arm nearest to you out at right angles to the body, elbow bent with the hand palm uppermost.

- Bring the far arm across the chest, and hold the back of the hand against the child’s cheek nearest to you.

- With your other hand, grasp the far leg just above the knee and pull it up, keeping the foot on the ground.

- Keeping the hand pressed against the cheek, pull on the far leg to roll the child towards you onto their side.

- Adjust the upper leg so that both hip and knee are bent at right angles.

- Tilt the head back to make sure the airway remains open.

- Adjust the hand under the cheek if necessary, to keep the head tilted and facing downwards to allow liquid material to drain from the mouth.

- Check breathing regularly (at least every minute).

- Ensure the position is stable. In an infant, this may require the support of a small pillow or a rolled-up blanket placed behind their back to maintain the position.

- It is important to maintain a close check on all unconscious children until the EMS arrives to ensure that their breathing remains normal.

- Avoid any pressure on the child or infant’s chest that may impair breathing and regularly turn the unconscious child or infant over onto their opposite side to prevent pressure injuries whilst in the recovery position (i.e. every 30 minutes).

- In certain situations, such as when the child or infant is breathing spontaneously but requires airway management or when the child has a traumatic injury, the recovery position is not recommended. In these circumstances:

- Keep the patient flat, maintain an open airway by either continued head tilt and chin lift or jaw thrust.

- For trauma victims, leave the child or infant lying flat and open and maintain the airway using a jaw thrust, taking care to avoid spinal movement.

Automated external defibrillators (AEDs)

- In children and infants with cardiac arrest, a lone rescuer should immediately start CPR as described above. In cases where the likelihood of a primary shockable rhythm is extremely high, such as in sudden witnessed collapse, if easily accessible, the rescuer should apply an AED (at the time of calling EMS). When there is more than one rescuer, a second rescuer will immediately call for help and then collect and apply an AED (if feasible).

- Trained providers should limit the no-flow time when using an AED by performing CPR up to the point of analysis and immediately after the shock delivery or no shock decision; pads should be applied with minimal or no interruption in CPR.

- If possible, use an AED with a paediatric attenuator in infants and children below 8 years (energy reduced to 50-75 J). If this is not available, use the standard AED (for all ages).

- There have been continuing reports of safe and successful use of AEDs in children less than 8 years demonstrating that AEDs can identify arrhythmias accurately in children and are extremely unlikely to advise a shock inappropriately.

Paediatric BLS in case of traumatic cardiac arrest (TCA)

- Perform bystander CPR when confronted with a child in CA after trauma, provided it is safe to do so.

- Try to minimise spinal movement as far as possible during CPR without hampering the process of resuscitation, which clearly has priority.

- Apply an AED if available, if there is a high likelihood of shockable underlying rhythm such as after electrocution.

- Apply direct pressure to any site of obvious bleeding to stop haemorrhage. Use a tourniquet (preferably manufactured but otherwise improvised) in case of an uncontrollable, life-threatening external bleeding.

- The management of the choking child with the sequence of reversing partial or complete obstruction of the airways remains unchanged.

- Back blows, chest thrusts and abdominal thrusts all increase intra-thoracic pressure and can expel foreign bodies from the airway.

- In half of the episodes documented with airway obstruction, more than one technique was needed to relieve the obstruction. There are no data to indicate which technique should be used first or in which order they should be applied. If one is unsuccessful, try the others in rotation until the object is cleared.

- Anti-choking devices: A recent systematic review focussed on these devices. Despite broad study inclusion criteria, the review identified only small case series, manikin studies, and cadaver studies, which were limited to a single device type. No reports of harm were identified, but their limited use in clinical practice means it is too early to conclude that their use is harm-free. The review recommended the need for further research before device use can be supported in practice.

- When a foreign body enters the airway the child or infant reacts immediately by coughing in an attempt to expel it. A spontaneous cough is likely to be more effective and safer than any manoeuvre a rescuer might perform.

- However, if coughing is absent or ineffective, and the object completely obstructs the airway, the child or infant will rapidly become asphyxiated. Active interventions to relieve choking are therefore required only when coughing becomes ineffective, but they then must be quickly commenced.

- Most choking events in children and infants occur during play or whilst eating, when a carer is usually present. Events are therefore frequently witnessed, and interventions are most often initiated when the child or infant is conscious.

- If unwitnessed, suspect foreign body airway obstruction when the onset of respiratory symptoms (coughing, gagging, stridor, distress) is sudden and there are no other signs of illness; a history of eating or playing with small items immediately before the onset of symptoms might further alert the rescuer.

- For as long as the child or infant is coughing effectively (fully responsive, loud cough, taking a breath before coughing, still crying, or speaking), no intervention is necessary. Encourage the child or infant to cough and continue monitoring their condition. Be reassuring in your manner when speaking to the child.

- If the child or infant’s coughing is becoming ineffective and or the clinical condition is deteriorating (decreasing consciousness, quiet cough, inability to breathe or vocalise, cyanosis), ask for bystander help and determine the child or infant’s conscious level. A second rescuer should call EMS, preferably by mobile phone (speaker function).

- A single trained rescuer should first proceed with rescue manoeuvres (unless able to call for help on a mobile phone simultaneously).

| General signs of choking | Ineffective coughing | Effective coughing |

|---|---|---|

|

Witnessed episode Coughing or choking Sudden onset Recent history of playing with or eating small objects |

Unable to vocalise Quiet or silent cough Unable to breathe Cyanosis Decreasing level of consciousness |

Crying or verbal response to questions Loud cough Able to take a breath before coughing Fully responsive |

If the child/infant is still conscious but has ineffective coughing, give back blows.

Back blows

- In an infant:

- Support the infant in a head-downwards, prone position, to enable gravity to assist removal of the foreign body.

- A seated or kneeling rescuer should be able to support the infant safely across their lap.

- Support the infant’s head by placing the thumb of one hand at the angle of the lower jaw, and one or two fingers from the same hand at the same point on the other side of the jaw.

- Do not compress the soft tissues under the infant’s jaw, as this will exacerbate the airway obstruction.

- Deliver up to 5 sharp back blows with the heel of one hand in the middle of the back between the shoulder blades.

- The aim is to relieve the obstruction with each blow rather than to give all 5 (hence may not require all 5 if successful).

- In a child over 1 year:

- Back blows are more effective if the child is positioned head down.

- A small child may be placed across the rescuer’s lap as with an infant. If this is not possible, support the child in a forward-leaning position and deliver the back blows from behind.

- If back blows do not relieve the airway obstruction, and the child is still conscious, give chest thrusts to infants or abdominal thrusts to children. Do not use abdominal thrusts (Heimlich manoeuvre) for infants.

Chest thrusts for infants:

- Turn the infant into a head-downwards supine position. This is achieved safely by placing your free arm along the infant’s back and encircling the occiput with your hand.

- Support the infant down your arm, which is placed down (or across) your thigh.

- Identify the landmark for chest compression (lower sternum approximately a finger’s breadth above the xiphisternum).

- Deliver up to 5 chest thrusts. These are similar to chest compressions, but sharper in nature and delivered at a slower rate.

- The aim is to relieve the obstruction with each thrust rather than to give all 5 (hence you may not require all 5 if successful).

Abdominal thrusts for children over 1 year:

- Stand or kneel behind the child. Place your arms under the child’s arms and encircle their torso

- Clench your fist and place it between the umbilicus and xiphisternum. Grasp your fist with your other hand and pull sharply inwards and upwards. Repeat up to 4 more times.

- Ensure that pressure is not applied to the xiphoid process or the lower rib cage as this may cause abdominal trauma.

- The aim is to relieve the obstruction with each thrust rather than to give all 5 (hence may not require all 5 if successful).

Following chest or abdominal thrusts, reassess the child/infant:

- If the object has not been expelled and the victim is still conscious, continue the sequence of back blows and chest (for infant) or abdominal (for children) thrusts.

- Call out, or send, for help if it is still not available.

If the object is expelled successfully:

- Assess the child or infant’s clinical condition.

- It is possible that part of the object may remain in the respiratory tract and cause complications.

- If there is any doubt or if they were treated with abdominal thrusts, urgent medical follow up is mandatory.

If the child/infant with foreign body airway obstruction is, or becomes, unconscious, move to treatment with the paediatric BLS algorithm.

- Call for help if it is still not available:

- Airway opening:

- When the airway is opened for attempted delivery of rescue breaths, look to see if the foreign body can be seen in the mouth.

- If an object is seen, attempt to remove it with a single finger sweep.

- Do not attempt blind or repeated finger sweeps – these can push the object more deeply into the pharynx and cause injury.

- Rescue breaths:

- Open the airway and attempt 5 rescue breaths.

- Assess the effectiveness of each breath: if a breath does not make the chest rise, reposition the head before making the next attempt.

- Proceed immediately to chest compression regardless of whether the breaths are successful and perform CPR.

- Chest compression and CPR:

- Continue with paediatric BLS using a C:V ratio of 15:2 (or the ratio you are familiar with) until help arrives or child improves.

- If the child regains consciousness and is breathing effectively, place them in a safe side-lying (recovery) position and monitor breathing and conscious level whilst awaiting the arrival of the ambulance.

Figure 1: Paediatric choking algorithm

ERC Guidelines 2021: https://cprguidelines.eu/

Executive Summary: 2020 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Nolan JP, Maconochie I, Soar J, Olasveengen TM, Greif R, Wyckoff MH, Singletary EM, Aickin R, Berg KM, Mancini ME, Bhanji F, Wyllie J, Zideman D, Neumar RW, Perkins GD, Castrén M, Morley PT, Montgomery WH, Nadkarni VM, Billi JE, Merchant RM, de Caen A, Escalante-Kanashiro R, Kloeck D, Wang TL, Hazinski MF.Resuscitation. 2020 Nov;156:A1-A22.

Pediatric Life Support Collaborators. Pediatric Life Support: 2020 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Maconochie IK, Aickin R, Hazinski MF, Atkins DL, Bingham R, Couto TB, Guerguerian AM, Nadkarni VM, Ng KC, Nuthall GA, Ong GYK, Reis AG, Schexnayder SM, Scholefield BR, Tijssen JA, Nolan JP, Morley PT, Van de Voorde P, Zaritsky AL, de Caen AR; Resuscitation. 2020 Nov;156:A120-A155

Couper K, Hassan A, Ohri V, Patterson E, Tang H, Bingham R,Olasveengen T, Perkins G On behalf of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation Basic and Paediatric Life Support Task Force Collaborators. Removal of foreign body airway obstruction: A systematic review of interventions. Resuscitation 2020; 156:174-181

Tibballs J, Weeranatna C. The influence of time on the accuracy of healthcare personnel to diagnose paediatric cardiac arrest by pulse palpation. Resuscitation 2010;81:671-5.

Dunne CL, Peden AE, Queiroga AC, Gomez Gonzalez C, Valesco B, Szpilman D. A systematic review on the effectiveness of anti-choking suction devices and identification of research gaps. Resuscitation 2020:153: 219-226